Costume dramas are a great source for accurate portrayals of how people acted and dressed in past times, right? HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA, no.

It’s not hard to think of all the ways movies and TV get historical clothing wrong, but let’s start with some of the more obvious ones. Because really, someone needs to point these things out, and that’s precisely what Frock Flicks is here for. So for Snark Week, let us review some of the ways movies screw up how people see historical costume!

Myth 1: Women’s Corsets Were Really Tight

When you’re all trussed up in a corset, you can hardly breathe! Corsets make you faint, they’re so tight. And of course you have to hold onto a bedpost to lace up a corset tight enough, right, Scarlett? Right?

Fact: Different types of corsets were worn throughout history, and various corset shapes provided different types and amounts of compression. This didn’t always mean they were tight or reduced the waist, even in the 19th century. A well-fitted corset was meant to be supportive and create a fashionable silhouette, not limit movement or restructure a body. Read how everything you know about corsets is false from Collectors Weekly and how wearing a corset affects you and your clothes from The Pragmatic Costumer.

Myth 2: Women’s Long Hair Flowed Free

Long, flowing tresses are the mark of purity, beauty, and femininity. Just look at those Disney princesses, and you know how historically accurate they are. Also look at all the lovely, grown-up ladies in movies from every historical period, from the middle ages through the renaissance to the Victorian era. Long, flowing hair. Why cover up all that prettiness with a hat?

Fact: For every one historical portrait of an adult woman pre-20th-century shown with long hair flowing down her back or shoulders (that isn’t allegorical or Biblical in intent), you can easily find 100 more images that show women with hair pinned up, styled, and often covered. Scroll through Wikimedia’s Portrait Paintings of Women by Century or Female Hair Fashion in Art categories for a sampling. You’ll find that the vast majority of women have their hair tucked up, plus they wear some kind of headgear. Throughout most of history, it was a sign of adulthood that women wore their hair up, and they also wore a cap or hat outside the house (men wore hats outside the home too before the mid-20th century).

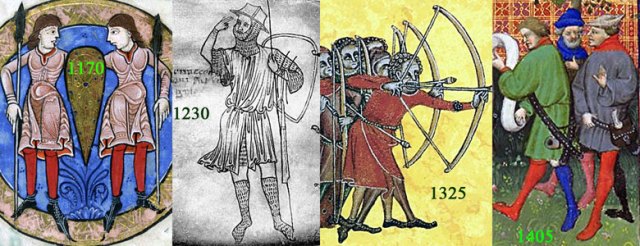

Myth 3: Men Wore Nothing but Tights

Men wore nothing but tights on their butts, especially in the middle ages. No pants required when you’re robbing from the rich and giving to the poor. Robin Hood’s era was all about the spandex leggings. Pants probably weren’t invented until cars were.

Fact: “Tights” were not like today’s spandex two-legged things. Hosen were made of wool, cut on the bias to fit each leg and foot, and the results could look a bit baggy. Most of the time, these hose were worn under tunics that reached to a man’s knees or lower. There was a point in the late 15th century when long hose were worn tied to a short doublet, and the crotch was covered with a rudimentary codpiece. This fashion evolved into the Elizabethan style with short, puffy pants, pointy codpiece, and elaborate doublet, worn with gartered hose. It was a relatively short period in fashion history that men wore only tights-like garments on the lower half of their bodies. For a whole lot more about historical hosiery, check out this annotated page on medieval underwear by Maistre Emrys Eustace.

Myth 4: Scots Wore Tartan and Kilts

From the dawn of time, every man, woman, and child in Scotland has been clad, head to toe, in their clan tartan. It’s a plaid, plaid, plaid world among them haggis-eaters. By the different tartans, you could tell who was from which clan or family, who they were related to, where their allegiances laid, what side of the bed they slept on, you name it! Most of all, real Scotsmen wore kilts and let it all hang out. You can take away our pants, but you can never take our freedom!

Fact: Scottish clan tartans are mostly a romantic 19th-century century invention. Woven plaid fabric did exist much earlier in Scotland, and different regions had their own specialty plaid patterns based on what vegetable dyes were available in that area. But the tartan wasn’t linked to families or clans until late in the game — the naming of official clan tartans began in 1815 by the Highland Society of London. Also, the kilt we all know and love has, at best, been documented to the very late 16th century in the remote Scottish Highlands, plus it was outlawed from 1746 to 1782. The 1814 publication of Sir Walter Scott’s first novel Waverley, which told a fictionalized version of the Jacobite Rising of a century earlier, helped create a fascination for all things Scottish, and this 19th-century revival is where we get most of our ideas about tartan and kilts from. Sorrynotsorry, Mel Gibson. Read more at the Historical Scottish Clothing Project by Sharon L. Krossa, PhD, from the Scottish Tartans Museum by Matthew Newsome, and the Evolution of the Kilt by Kass McGann.

Myth 5: Servants Had to Be Dressed Identically

They kept those outfits perfectly, crisply clean too, even if one was the scullery maid. From the smallest house to the largest, your servants were dressed in matching outfits, and sometimes they even wore your personal badge or mark on them. Because the world had to know who their boss was.

Fact: Servants were a lot more ubiquitous throughout history than we realize today — you didn’t have to be super-rich to have a servant in the home. Most everybody needed and hired help. Also, tons of people needed jobs, especially women and young men, so domestic service or farm labor were common employment. In some periods and places, servants could be upper-class young adults out to get more experience in the world. Employers might provide clothing as part of the servant’s payment, but they might not. The clothes might match other servants or be liveried (show the employer’s heraldry), or they might not. It varied wildly from person to person and over time. In England and America, domestic servants became a status symbol in the 19th century and thus dressed more formally. Before that, a servant wore whatever clothes they had, with the addition of an apron or any gear needed to do her or his job. Find out more from Up and Down Stairs by Jeremy Musson, Domestic Service in the Hidden History of Kent, and the books The Queen’s Servants and The King’s Servants.

This is barely the tip of the iceberg for how movies get historical costume wrong, of course! We can’t possibly list every single way Hollywood screws up people’s understanding of period fashions — but we’re trying. Stay tuned for all of Snark Week, where we’ll look at some of our favorite terrible historically inaccurate costume dramas and show exactly how movies and TV get different types of historical clothing wrongity-wrong over and over again. Chime in with your faves too!

Cannot imagine wool ‘tights’ being at all comfy.

Wool fabric comes in many different varieties & a range of weaves. Unless you have an actual wool allergy, wool isn’t automatically itchy. It’s been used as undergarments forever & still is!

Check out this article praising the wonders of merino wool women’s panties:

http://offbeathome.com/2013/11/merino-wool-underwear

not only are they comfy, braes are DAMN SEXY on men ::faints::

My spouse did Civil War re-enacting for a while, and it was wool, wool, wool. I washed the wool before making the garments — no itch! Best part, he could keep washing it without any shrinkage.

Among the many culprits of misguided information on matters historical in general were the Victorians, especially the painters, who tended to portray historical clothing along contemporary lines. Sir Walter Scott may have publicised the Scots, but he also romanticised them to an absurd degree. A particular set of Villains in the tartan tangle were two guys named “Sobieski-Stewart,” who published “Vestiarum Scotiorum,” a nice piece of whimsy about clan tartans, etc. In this regard, see George MacDonald Fraser, “The Steel Bonnets,” a history of the Borders, and “The Hollywood History of the World.”

The one that always irritates me movies featuring modern militaries (mostly 20th Century) is when the haircuts are completely wrong and nobody wears a hat or helmet when they should be. One of the worst offenders is Brad Pitt in “Legends of the Fall” when he joins the Canadian Army to fight in France with his brothers and he keeps that long hair. Sorry, no hippies in 1915.

ALL THE HAIR in Legends of the Fall. Wait for next week, Snark Week 2: Electric Bugaloo!

Made me want to grab a set of electric sheers and go to work…

The first step in enforcing conformity and discipline on new recruits is cutting the hair.

Wool — I have several pairs of Scottish Regimental trews — the relative softness, feel, and comfort of each pair is quite different to the other. Lamb’s wool can be quite as soft and comfortable as the finest cotton.

It was also a matter of hygiene with lice and such. Moreover, excessive hair doesn’t allow for a good seal while wearing a gas mask, something that was of critical importance.

Nothing destroys credibility of military chapters quicker than improper groom and incorrect uniforms. It’s not like the information isn’t out there. :-)

The best out there I’ve seen so far is “The Duelists,”which not only got the details of uniforms and hairstyles, but showed the changes over time. Consultants were the Mollo brothers who have written several excellent books on historical uniform.

I’ll give that scene in Shakespeare In Love a pass re: loose hair, because Viola is playing Juliet and it’s not too far-fetched to imagine using loose hair as part of the costume to emphasize the character’s youth and purity (and femininity, since everyone thinks the role is being played by a teenage boy). In other scenes like the ball or meeting with Wessex in the red dress, though, there’s no excuse.

I did a masters degree which partially looked at whether period dramas should portray accurate period costume or whether they should be less about accuracy and more with current aspects. When I started the research I was very much that they should be accurate. Of course that’s what those of us interested in costume would like to see. As the research went on I realised no one would want to see accuracy, it’s sometimes less attractive, less camera friendly or flattering. For example Jane Austen dramas of the 90s. The make up would be very unattractive. Actresses would look larger due to the accurate petticoats. John Bright designer of Sense and Sensibility told me that the key actresses wanted to appear smaller and for this reason accuracy was ignored. I found that when looking back at period dramas you can always tell which decade they were filmed in by hair, make up and silhouette. It’s how people today can relate, and maybe a little subconscious. Entertainment is about relating to the populous and making money ultimately. Accuracy is for museums and not tv/film. Personally I would love to see accurate representation xx

“when I started the research I was very much that they should be accurate. Of course that’s what those of us interested in costume would like to see. ”

and those interested in language would also like to see the correct language used, like the story about set in 15 century England should use 15th century English as the language and story set in French court should use French and not the language of the country of the production company.

but as you have said the rest of your post, it is all about being relatable.

so the complains about the incorrect costumes, incorrect sword fight and incorrect languages are all much ado about nothing actually.

Don’t be ridiculous! We have the ability these days, thanks in large part to the HEMA (Historical European Martial Arts) movement to know what correct historical swordsmanship is like; we have many good costume references and examples in museums. But the majority of us don’t have the ability to speak an historical language. So our “complaints” are not much ado about nothing; they are much ado about getting right what can practically be gotten right.

I don’t see the problem. Many interesting stories of humankind came from interpreting past story tfrom the view of the period when the story was being told.

Arthurian legends tell the story about 5th or 6th century England through the perspective of High Middle Age and beyond. The concept of knighthood is a huge part of the legends even though that was not really a thing in 5th or 6th century England. Who to say the 1981 Excalibur movie is not a good movie?

Not to mention the Shakespearean plays were interpreting old tales through contemporary Elizabethan lense.

Human culture would be a lot poorer without those stories.

Legends are legends because they contain an enduring truth that isn’t tied to a time or place. But if you’re claiming that a film takes place in a given time and setting, then the more accurately that can be reproduced, the more educational as well as entertaining it can be.

My current curmudgeonly irritation focuses on Netflix’s “Father Brown”. They get so much of the 1950s perfectly. They get Fr Brown’s outfits perfectly — except for the fact that priests usually switched from cassock to suit when traveling. But for the bishop the outfit is some weird, made-up fantasy. It’s as if someone looked at a Renaissance painting and said “Ok. Maybe a bishop looks like this.” They could have bought the real thing on eBay for 50 GBP!

On Myth 4- I also heard that most of the upper classes of Scotland were more likely to look like their English neighbours, in pants {whatever the period-correct equivalent to ‘pants’ happens to be}, than kilts- or more accurately earlier, ‘kilted plaids’.